The International School in Mathare (informal settlement of Nairobi) constitutes a rare opportunity for the 134 refugee and vulnerable local students currently enrolled. Beyond the access to quality education, the school also gives them a space where they can explore the possibilities that the world can offer while feeling protected from the risks that surround them.

Unfortunately, reality has struck one of our students hard, as he lost his father due to the injuries suffered in a traffic accident. Ernest*, a 35-year-old Burundian refugee, lived in Nairobi with his children after fleeing the political crisis in his home country.

A few months ago, while riding his motorbike through the streets of Nairobi, another driver encroached on his lane, pushing Ernest into a matatu, a very common public transport service in Kenya but of private ownership. The collision caused a minor concussion, a cut on his head and a severe blow to his chest, and the man was unable to move until a friend came to pick him up to take him to hospital.

From this moment on, Ernest and his family could not find proper attention to his symptoms that got worse by the hour over the course of three days. Indeed, just in the evening of the accident Ernest had to visit four different hospitals before feeling some relief from his pain. Initially, the man was simply given painkillers and anti-inflammatories and was coerced to wander around different medical facilities almost begging for assistance.

Only when he could barely breathe he underwent a small operation to relieve the pressure of his lungs through a catheter.

However, no medical doctor was apparently able to read the X-Ray and diagnose him correctly. The reason for Ernest’s pain and ultimate cause of death was a diaphragmatic rupture that led to respiratory failure due to lack of treatment and monitoring.

In any case and despite his obvious suffering, Ernest was never admitted to the hospital and was only treated in the emergency room alongside other patients, without any privacy or basic hygiene measures. Obviously, the intervention did not help Ernest to heal and may have even exposed him to further risks.

When the family left the hospital the day after the intervention, they were assured that Ernest would be taken care of and that he would feel better after a night’s rest. Quite the contrary, they found only an empty bed the next morning and the news that he had passed away during the night was communicated by the patient lying next to him.

As a first step to seek redress for our student, Still I Rise has coordinated with a Kenyan lawyer and has presented a formal complaint at the Kenyan Medical Practitioners Council against the hospitals on the charges of medical negligence.

Since national law does not allow to directly present criminal charges against medical practitioners, this is the only way in the Kenyan system to hold the doctors accountable and potentially having their medical licence withdrawn, as well as the hospital’s.

Although the 2010 Constitution of Kenya determines the right to health for every person, refugees continue to experience unique barriers in accessing healthcare. For instance, they report discrepancies in healthcare cost in comparison with local Kenyan clients, requirements for documentation before service, threat of harassment, and language barriers.

Nevertheless, the cost of health constitutes a major barrier for all the population in the country. Kenya has developed over the years a solvent healthcare system, but only very basic services are provided free of charge. Public and private services coexist, both requiring the subscription to some kind of insurance in order to grant full coverage to the users and to avoid incurring exorbitant medical debts.

Although, in theory, refugees are legally able to apply for work permits that would grant them access to some kind of insurance, in practice this is difficult to achieve given the legal framework, the encampment policy and the bureaucratic processes required.

Economic inclusion of refugees and asylum-seekers continues to be hampered by their lack of access to certain platforms critical for obtaining documentation to facilitate such inclusion. A more recent 2019 study found that major barriers to accessing health care persist among urban refugees in Nairobi. These include language, location, cost, provider attitude, discrimination and lack of National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) cards/health insurance, with cost being the most important barrier.

Additionally, the prevailing refugee encampment policy in Kenya that prohibits refugees from leaving the camps has resulted in a situation where many refugees in urban areas are not registered with the relevant refugee agency.

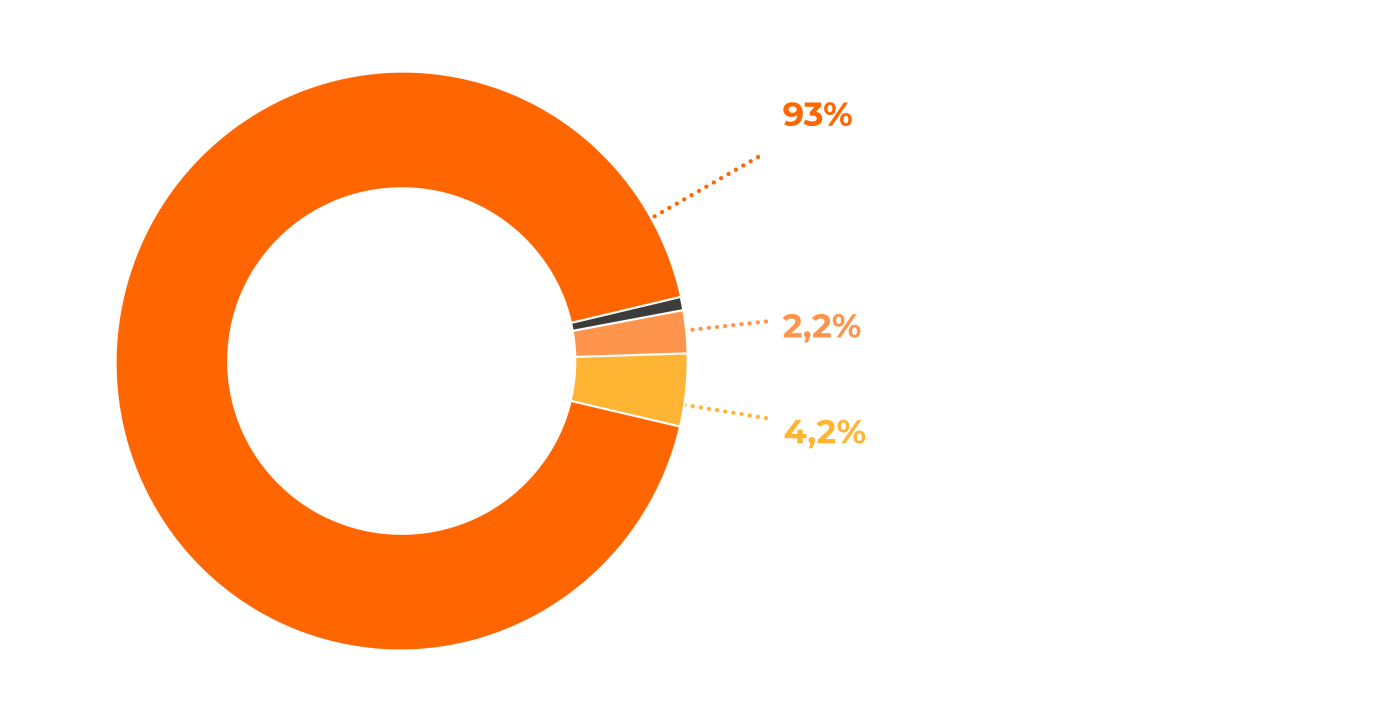

New hopes for social and economic inclusion of refugees in Kenya have risen after the approval of a new law that will allow them to work and break the circle of dependency on humanitarian aid: a necessary step towards integration as the Kenyan government advances towards the closure of the camps where four out of five refugees currently live.